Don't Try This At Home

A few months ago I found myself with a fun little problem and decided to solve it in the most insane way I knew how.

Background

I was maintaining PyBloqs, an open source framework for creating data-heavy reports from python. The specifics are not important to this story, but I’d recently added a dynamic server to the project.

In a nutshell, users could define dynamic dashboards similar to streamlit or dash, but much simpler. PyBloqs’ mantra is “good enough” so it isn’t particularly fully featured.

Under the hood, its simply a flask server which serves snippets of HTML on various endpoints. The main pages then have shims that use HTMX to load the content from these endpoints and populate the dashboard.

There’s plenty more, such as self-refreshing blocks, and resource management that I won’t get into, but you can read the code to see the the problems I had to solve, if you are so interested. The point is, URL parameters and headers are important to the proper functioning of a dashboard1.

This was all a fun little problem to solve and I was very glad to be allowed by my employer to open-source the result, but it isn’t the topic of today’s blog post.

That would be the hard part: documentation.

Show, don’t tell

Its one thing to describe an abstract dashboard in words, but quite another to actually show it. I decided that, in order to convey to the reader the primary (as I saw it) advantage of PyBloqs server - its simplicity - each part of the documentation would show the code for a dynamic report above the report itself.

You can see the result here.

From static to dynamic

This presents a couple of problems. Firstly, the documentation is hosted on readthedocs so we only have static hosting. Secondly, we’d need to stand up a server to actually serve the dynamic reports.

The first problem is easily solved using <iframe>s. Each demo dashboard would just be a nested browser window pointing to https://our-server/dashboards/awesome_demo_32.

The second is slightly more tricky. For reasons we didn’t want to have a dedicated server just for the documentation page. We could (almost) fake it by having static files served as if they were dynamic endpoints, but our demos involved “live” components such as the time. Also, it keeps you honest if you genuinely use the tool to do the Thing you claim the tool is good for.

The other 90%

But if we couldn’t make a request to some server out there for our demo dashboards, we were going to have to fake something. The code would have to run on someone’s computer. What if it ran on the reader’s computer? If we just gave them the code to run and got them to expose localhost:8080 or something then we could point at that.

For reasons that will be apparent later, we won’t want each iframe separately making requests to localhost:8080 or whatever. We’d like to intercept those requests and redirect them from one place.

Here we get a bit lucky. While you can’t intercept HTTP requests made from child <iframe>s in the parent browser window, you can intercept requests made from your own window. So, to each of our dashboards in our sample script, we add a small shim that uses xhook to capture the HTTP requests and turn them into messages to our parent window.

Then we can listen in the parent for messages, make the HTTP requests to something like http://localhost:8080/awesome_demo_3/sub_element and pass the response back to the iframe using messages again.

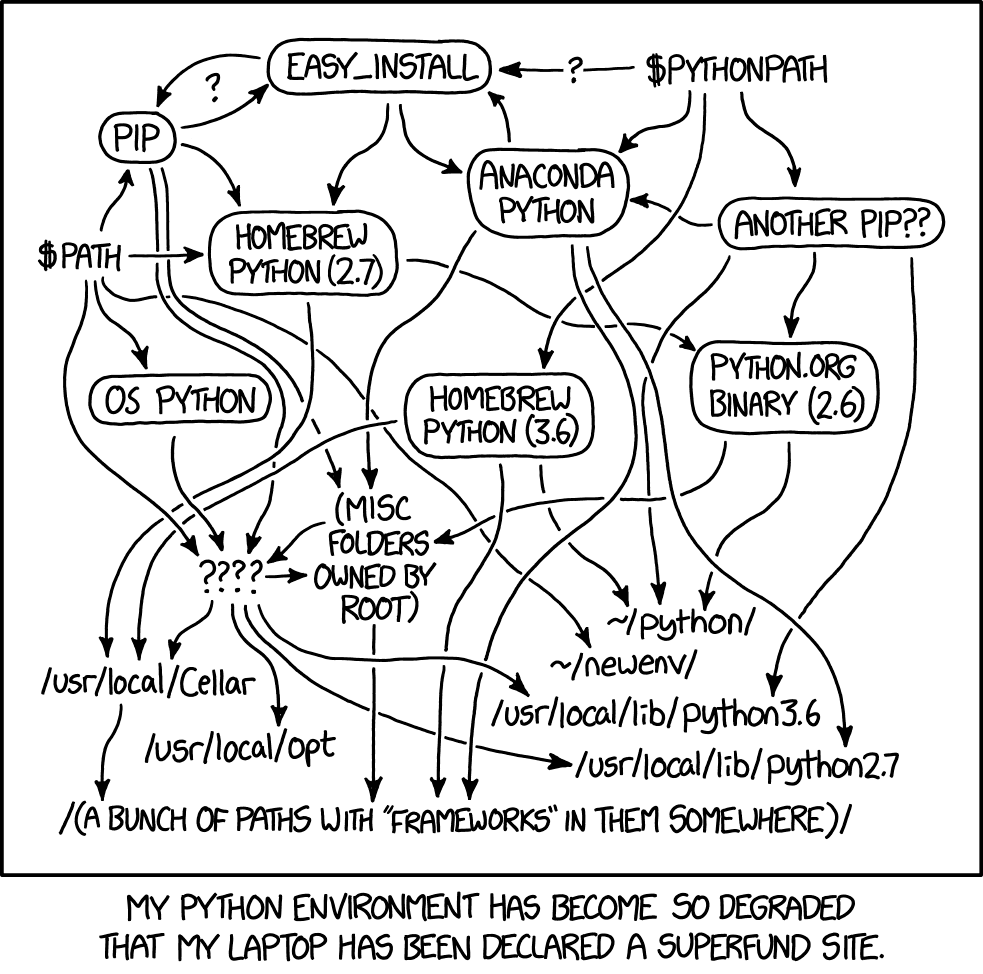

So far, we haven’t solved anything. We still need the user to download the source code, stand up a virtual-environment, install a bunch of dependencies and then run the sample script. At the best of times reproducible environments are nearly impossible3 as XKCD notes:

What if we could do that for the user? Choose a python version, set up a venv, download our code and run it? What if it worked on every architecture, operating system and distribution? What if it ran in the browser?

To cut to the chase, this is where Pyodide shines. Pyodide is a port of CPython to webassembly so it runs in the browser. It also ships with micropip which lets you install python packages to the browser window (‽) and call python functions from javascript.

At last we have our flow: we’ll install python, pip install pandas and all the other packages we need (including the PyPI distribution of PyBloqs to keep us extra honest) and run the script using

pyodide.runPython(await (await fetch("../server_demo.py")).text());

Then we can use the following function to make HTTP requests to our flask server called app in server_demo.py.

let app = pyodide.globals.get("app").toJs();

function forward_request(method, route, headers) {

return app(method, route).toJs();

}

There’s a bit of extra stuff that goes on to convince the WSGI app to just return a string of output, but its very similar to standard testing harnesses.

The JPEB stack4

So we have achieved what we wanted to do: the user’s own browser is acting as the server to serve the dynamic content (via HTTP over… window messages?) to the dashboards. On the page, we tell a white lie and ask the user to wait while we are “Spinning up a pybloqs server just for you”5.

I like to think of this as the JPEB stack - Javascript, Python, Emscripten and Browser. A new horror for the web.

As ever. Don’t do this. You almost certainly have no reason to.

-

If it seems odd that I’m mentioning that, just wait. ↩︎

-

In fact, for reasons that will become clear soon, it was just

src="/mixed_report"or similarly named dashboards. ↩︎ -

In contrast to the LAMP stack. ↩︎

-

Perhaps it should say “Please wait while you spin up a server for yourself.” ↩︎